This has already happened.

Napo is living an unwelcome déjà vu.

In Ecuador, news of the massive, accelerated loss of the Jatunyaku River in the Yutzupino area was sudden. Between October 2021 and January 2022, illegal mining expanded the equivalent of 99 professional soccer fields.

As a result of social pressure exerted by communities and organizations defending environmental rights, on February 13, 2022, at 1 o’clock in the morning, a major law enforcement operation was carried out on what was left of the river. The Interior Minister, the Minister of Defense and 1,600 uniformed members of the National Police and the Armed Forces arrived at the site.

Among the huge craters and mountains of debris, in what was once a crystalline tributary of the Napo River, 148 backhoes, 97 water suction engines, 16 water pumps, 80 mineral separation machines, known as "Zetas", 41 265-gallon containers with fuel, and other assets used to extract gold were seized.

On that February morning, photos, videos and aerial images of the biocide were made public. There were people arrested who were later released.

In May 2023 at the entrance to Tena, the gateway to Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, a pile of seized, stranded backhoe loaders still stood, as if welcoming visitors.

Tena is the capital and largest city of Napo Province, a region rich in biodiversity, surrounded by lush tropical hills and rivers that attract tourists seeking kayaking adventures and jungle treks.

According to the Ministry of Tourism (MINTUR), there are 318 tourist attractions in Napo. Most of them are archeological sites (81), followed by waterfalls (68), scenic overlooks (15), and caves (14), such as the well-known Jumandy.

That makes tourism the second most important source of economic income in the province after agriculture. One of the main tourist activities is Ziplining, once a favorite attraction on the Jatunyacu River, which has now almost disappeared.

More than two thousand people worked in Tena between October 2021 and February 2022 in the illegal extraction of gold, according to social organizations and environmental defenders. Even though the unexplained appearance of the first four backhoes in November 2021 on the banks of the Jatunyaku River attracted the attention of environmental activists who denounced them to the Governor's Office of Napo and even through social media, they received no response. From the Los Ceibos scenic overlook, one could clearly see the increase in the number of orange machines, which went from 4 to 10, to 50, to 100, to 148.

The Los Ceibos scenic overlook was the first to be shut down. No one knows exactly who put the yellow tape with the word danger in black letters at the entrance and, if they knew, they would not say so. Backhoes went through there to clandestinely enter the Jatunyaku River. Currently, at the junction of the Troncal Amazonica highway with this secondary road, there is a police checkpoint. But fear, doubt and distrust remain among the inhabitants.

People in the area said they were paid between $2,000 and $2,500 to allow the backhoe loaders to drive over their land. That money was also intended to buy their silence.

Oliver* (name protected) was 17 years old when the destruction of the Jatunyaku River began in 2021.

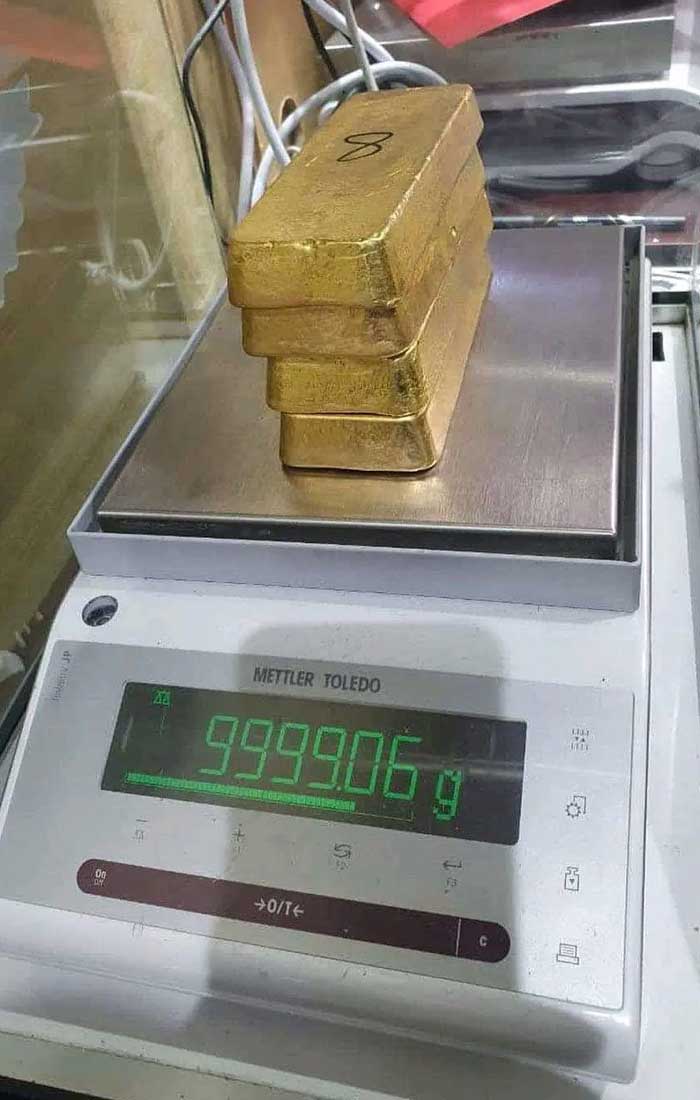

“If you got under the backhoes, wherever you walked you would find gold,” he says as if it was one of his first juvenile feats. “Sometimes they made us pay a dollar to enter to extract gold, but it was worth it. That was at the beginning. Then more and more people began to arrive, some say there were thousands. I saw pregnant women, children, adults. We were pushing each other to get the gold. I was lucky, I earned a few thousand dollars,” says Oliver with an innocent smile.

― And what was the process like? Who were you selling the gold to?

“An old man who had a store in Tena. He was the only one with whom you could exchange gold for cash.”

― You were young. You were 17 when the Jatunyaku was looted. Were you afraid?

With childish mischievousness, Oliver smiles and accepts that he was afraid at first but later thought that if everyone does it, why should he be left without gold?

“My mother told me not to go. But we were a poor family, and all of a sudden, we had a lot of money under the mattress.”

― And what did you do with that money?

“We sent my sisters to another city so they could buy a house and get out of here. I don't leave because I don't want to leave my parents alone. We couldn't have much money here because they used to come and confiscate it when they started carrying out raids.”

― Did you make that much money?

“Ufff, yes. Just imagine. On a good day several grams of gold could be extracted. One had to pull one's socks up because otherwise, they could follow you to steal from you. There were cases in which neighbors swindled each other.”

― Were you ever robbed?

“No, because I learned to be cautious. One night I found a piece of gold this big (he says by separating his smooth, tanned hands in the air about 4 inches). So, do you know what I did? I went into the woods, around 11 o'clock at night. Slowly so as not to make any noise. Looking everywhere. I went deep and stayed hidden in a tree, very quiet, with the gold in my hands. I stood almost like a statue. For three hours! Until I was absolutely sure that no one followed me. There, at about 2 o'clock in the morning, under the moonlight, I buried my gold. Only I know where it is.”

As the walk and conversation with Oliver continue, near the new scenic overlook, a man appears. Oliver immediately starts talking about birds and what tourist site he recommends in the area. The man walks to the scenic overlook. As he disappears, Oliver whispers that this person belongs to the "intelligence group of the miners.” They are everywhere, he whispers, and they "tell the boss everything.” They don't like it when people or journalists come here and ask questions.

State's inaction

In March 2022, days after the Yutzupino disaster, twelve collectives from Napo filed a protective action against the Ecuadorian government for lack of regulation of mining concessions. They won in the first and second instances. On April 13, 2022, the judge of the Provincial Court of Napo ordered the Ministry of Environment, the Ministry of Mines, and the Agency for Regulation and Control of Energy and Non-Renewable Natural Resources (ARCERNNR) to present within 180 days a reforestation plan for the areas affected by illegal mining throughout the province.

The authorities have not complied with the sentence.

In January 2023, the collectives filed a new lawsuit for non-compliance with the previous one. Again, the judge of the Provincial Court of Napo agreed with them and ordered the dismissal of the three ministers, the reparation of the affected areas, and set a deadline of 48 hours to present a reforestation plan. There is still no response from the government and no one has been dismissed.

On April 13, 2023, the National Assembly approved with 121 of 137 votes, the Report on the Inspection and Monitoring of illegal mining in Napo, in the area of Yutzupino. The document acknowledges the ineffectiveness of the government and the great social and environmental damages in a radius of 12 miles around the Jatunyaku River, known as "Ground Zero.” The Resolution of the National Assembly is binding and includes 36 obligations and immediate actions that several Ministries should have fulfilled to stop the Yutzupino biocide.

Such obligations include that within 60 days, the President of Ecuador should reform Executive Decrees 754 and 151 related to mining.

The Ministry of Energy and Mines was obliged to restructure the Regulatory, Control and Surveillance National Agency in a maximum of 60 days. This did not happen. They only changed its director, who told said through its Communication Department, that he will give interviews when he is more familiar with the issues.

The Ministry of Energy and Mines has 90 days to submit to the National Assembly a geological report and a new regulation to improve inspection processes. And in that same period, it must request technical and legal reports of the Regulatory Agency for the extinction of mining rights.

The Regulatory, Control and Surveillance National Agency was required, within 30 days, to hire six mining monitoring and inspection specialists for the Napo province alone.

The Ministry of Environment and Water was given 30 days to create environmental damage determination processes.

The Ministry of Public Health was given 30 days to carry out a study of the level of impact on the population caused by mining activities.

The Ministry of Transportation and Public Works was given 30 days to regularize all machinery and backhoes and ensure that they have GPS installation certificates.

"Nothing has been done. Nothing. Sometimes I am disappointed by this nonsense that does not end in anything concrete, measurable, tangible," said Andres Rojas, the Ombudsman of Napo, on May 18, 2023 -- the day after Ecuador's President dissolved the National Assembly.

Rojas is following up on compliance with the Resolution Report for which they fought so hard. He says that the last thing he was told by the Presidency was that it had not yet received the notification.

The Ministry of Environment responded that they are analyzing the situation and that this is all they can say. The response was similar in the Ministry of Mines. The Regulatory Agency claims that to date it knows nothing about this Resolution. The Ministry of Transportation has not provided any response so far. Several heads of the public institutions were not aware of the Resolution based on the inspection report and requested a copy of the document in order to understand what it is about.

Gustavo Redín is a lawyer who is an expert in environmental issues and a member of the Ecuadorian Coordinator of Organizations for the Defense of Nature and the Environment (CEDENMA), which brings together several Ecuadorian environmental organizations. He recalled that not much can be expected if the inspection entity that issued the Resolution, the National Assembly, no longer exists.

Despite this, despite everything, despite the raids, the news, the lawsuits, the gold flow, and the environmental devastation, Napo is going through a second biocide.

A greater disaster has emerged and it's going unnoticed

“Please don't say my name.” The phrase is repeated by people who live close to and have even denounced the mining operations.

Alberto* is a native of the Huambuno River area. He works in ecotourism. He is part of an ancestral community that does not agree with mining.

In front of his property, across the river, he has seen an increase in the presence of backhoes digging more than 30 feet into the ground to extract gold, destroying everything in their path.

Alberto has been documenting this activity for years with photos and videos. He was held at gunpoint one afternoon last year for doing just that.

“A man came, pointed a gun at me, and told me that if I continue to denounce them, he is going to kill me and throw me like a dog in the street or in the river. At that moment, I thought he was going to shoot me, but he didn't.”

The case is complicated and is being investigated by the Attorney General's Office. Alberto has documented the presence of 18 mining fronts with more than 80 backhoes on the Dorado-Huambuno-Cashayaco-San Pedro de Huambuno, Alto Huambuno, and Rio Blanco routes. He says the machines work night and day.

“They are destroying the river we used to drink from and bathe in. Water pollution started. Frogs, birds and all the biodiversity were affected. There was never any socialization or training. The machines appeared overnight. I have filed a complaint and my uncles and aunts also filed seven more complaints, but technical assessment was never carried out and everything is at the Quito Prosecutor's Office,” says Alberto with nostalgic voice.

A study by the Ikiam Amazon Regional University has demonstrated that in Napo there are dead rivers such as the Chumbiyaku, which has 500 times more heavy metals than the permitted limits. The study also indicates that in the areas affected by gold mining, the soil erodes, loses organic matter and the gradual drainage of contaminating waste descends to lower layers of soil, making the land toxic and infertile.

Families in the Ahuano area, near the towns of Huambuno Alto and Río Blanco, have reported skin damage from bathing in the Napo River.

The community of Río Blanco split. Five families created a new community called Ñucanchi Urku and gave way to mining. Alberto names the Napu Kury, Huambuno 1, Huambuno 2, Huambuno 3 and Emprendimiento Minero Familia Romero concessions.

Napu Kury is not on the list of operators registered at the Ministry of Energy and Mines. Emprendimiento Minero Familia Romero is concessioned to Ivan Romero.

Huambuno 1, Huambuno 2, and Huambuno 3 are concessioned to Transconmi Construcciones Cia Ltda. The current legal representative is Nelson Ashanga. The founder, General Manager and shareholder of this company from 2010 to 2021 was Telmo Andres Bonilla Abril, former mayor of the Archidona canton, in the province of Napo. According to the Superintendence of Companies, Transconmi's purpose is not mining but road construction.

InquireFirst attempted to contact Bonilla, but did not get a response. InquireFirst did not receive a response from the company by phone or by the email (Yahoo) that Trasnconmi has registered with the Superintendence of Companies, which coincidentally is the same contact email of Terraearth Resources.

Terraearth Resources is a mining company funded by Chinese capital that has several concessions for the extraction of gold within the province of Napo. However, it has received several notifications from the Ministry of the Environment due to environmental breaches, and it continues to operate.

The Single Environmental Information System (SIUA) of the Ministry of Environment has three environmental license requests for the three Huambuno concessions. The last one is recent (dated April 23, 2023). All of them were archived, which means that they did not meet the parameters for obtaining the environmental permit. However, there are machines operating on site.

According to Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP), in 2022 the expansion of the mining area in Huambuno was 86.1%. Between January 2022 and January 2023, 272 acres of jungle and agricultural areas were destroyed. This is double that of Yutzupino, where mining expanded by 135 acres between January and December 2022, according to a new MAAP estimate.

If Yutzupino was a biocide, Huambuno is a bigger one. That is why Fiodor Mena, president of the Association of Environmental Engineers of Ecuador and member of the Council for the Defense of the Rights of Nature, believes the government should declare a state environmental emergency in the province of Napo.

But so far there have been no major actions in the area, and neither the ministers, nor the police, nor the military have intervened. Those who denounce the situation live amid threats.

In 2022, the Regulatory Agency carried out 348 raids against illegal mining throughout the country. Of those, only 20 were in Napo, despite the surge in the growth of mining fronts in this province. The total number of raids is 17% lower than in 2019, when 418 were carried out nationwide.

Among the causes that Fiodor Mena mentions for the disaster of Napo's rivers is institutional weakness. According to report by the Biodiversity Commission of the former National Assembly, until 2022 there was only one mining technical specialist who had to control 552 registered mining concessions and 171 in process distributed in three provinces: Napo, Orellana, and Pichincha.

In addition, this technician had to carry out administrative procedures and reports. Many reports.

The same document from the Assembly states that there are many pending procedures at the Regulation Agency: 275 pending procedures in the Quipux system, 190 semi-annual production reports, 165 annual exploitation and production reports, in addition to citizen complaints and accompaniment to control raids requested by the Ministry of Environment, the Public Prosecutor's Office and municipalities, among other institutions.

According to Mishel Báez, a university professor and political scientist who specializes in environmental issues, the government is allied with the mining sector. "The government defends the interests of mining capital and vice versa. In fact, there are rewards such as important positions in the companies after leaving the public sector. It is a very common practice that employees of extractive companies get to public positions and then return to better positions in the company. This is called the revolving door effect. In these exchanges, the government and the mining industry live in constant collusion," she says.

The revolving door effect allows information, agreements and negotiations to be brought back and forth between the private and public sectors. For this reason, countries such as the United States and France have implemented laws that allow for a "cooling-off period,” which lasts from one to three years, during which an official cannot work in important positions in the same sector, and vice versa. This is a way to mitigate a conflict of interest.

In Ecuador, a revolving-door law was proposed. The debate on the proposed law took place in the Plenary of the Assembly, lasted less than two hours, and was shelved by majority vote on March 24, 2022.

Mining without a road is not mining

"I am scared," said Gonzalo,* who lived 10 minutes away from Alberto's community, on the other side of the Napo River.

Gonzalo was a tour operator and in September 2022, between departures and arrivals of tourists in boats, he noticed that, in front of his property, heavy machinery was openly diverting the Napo River at the mouth of the Arajuno River. Visitors began to complain about the deafening sound of the machinery that operated 24 hours a day. Some left upset, others surprised.

Hanging bridge over the Arajuno River. Photo/Shutterstock

Gonzalo took photos and videos and uploaded them to social media. The area that was being removed was a sandbank, which was part of the community of Balzachicta, where there is a concession for the extraction of rocks, sand, and minerals that belongs to the Napo Provincial Decentralized Autonomous Government. This concession did not yet have the environmental permits to operate and was not yet registered at the Ministry of Energy and Mines. However, since September 2022, dump trucks, backhoes, and material sorters have been increasingly arriving at the riverbed.

Gonzalo monitored day by day the progress of the extraction of stone material in this sandbank. He sent letters to the Ministries of Tourism, Environment, Mines, and the Attorney General's Office.

On December 5, 2022, the Zonal Environmental Directorate suspended the operations of the concession due to infractions such as:

- Not being registered as a hazardous waste generator

- Contamination and diversion of the Napo River channel

- Not having administrative permits

Fiodor Mena was the regional director of the Ministry of Environment at the time and confirms that they did not have all the administrative acts up to date. That is why he gave the suspension order.

But the machines continued to operate.

On January 31, 2023, the Minister of Tourism, Niels Orsen, urged three officials -- Magistrate of Napo Rita Tunay, Director of the Regulatory Agency Luis Maingon and Mayor of Tena Carlos Guevara -- to take precautions when carrying out infrastructure works. He pointed out that the Napo River, along with others, was declared a "site of tourist interest" in 2020, and said the existence of resources and attractions must be considered during a petition or the issuance of environmental permits for the extraction of stone and mining material.

A week later, the Prefecture responded by confirming that it had already requested all the permits and that the material extracted from the Balzachicta GADP concession in Napo is being used for an important project -- "the nine miles of asphalt on the road from the Rio Pusuno – Ahuano, third stage, longed for by many residents.”

On March 1, due to insistent complaints on social media from some residents such as Gonzalo, the government was forced to close the Prefecture's machines in a large operation due to administrative and environmental non-compliance.

Despite this, the machines continued to operate on March 2.

Gonzalo denounced this constant non-compliance in various media until cantonal and parish authorities in favor of mining met with residents to convince them of the benefits of the new road.

In an assembly that was recorded, local leaders said that indigenous justice must be applied to foreigners who interfere in the decisions of the province (Gonzalo is not Ecuadorian). He received four death threats, which forced him to leave the country. When he talks about everything that has happened, Gonzalo cries. He feels like he is living in exile.

Jose Punzhi grew up between the Napo River and the jungle in the community of Balzachicta. Part of his land was invaded, first by mining operators in August 2022 and then by the Prefecture. He was never asked for permission to operate machinery on his land. The miners in the area told him that these lands already had another owner and Punzhi started legal proceedings.

“The miners, who claim to be businessmen, are dividing the people. They buy people. The mining operators offer everything to the community, believe me. I grew up there, I was educated there, and I lived there with my parents. Those lands belong to us. The miners came to offer the community leaders 15% of what comes out of the gold, compensation work, and to provide jobs for the people. Then they offered them a party with food and drinks. The conscience of a part of the people -- bought! They didn't take us into account. They were supposed to ask all of us who own property there. There are about 40 families and of those 40 families, most of them had a party. We filed complaints and we were able to suspend the mining operations because they did not have permits. From Balzachicta some of these so-called businessmen went down to Huambuno.”

Then came the issue of the extraction of stone material.

“My neighbors told me that this extraction by the Prefecture was suspended. It was for asphalt work supposedly to improve the road. We are not totally blocking the extraction of material, but we want responsible mining. What we are seeing is that they mine as they want. There are people who do not want to commit (to demand responsible mining) because they are afraid. My two neighbors did not sign the complaint, they told me they did not want to have problems," says Punzhi.

According to documents of the Autonomous Provincial Government of Napo, the "maintenance of the Ahuano - Pununo road ring,” was awarded to CONSORCIO RÍO PUSUNO AHUANO on May 26, 2021, for $7.4 million to put asphalt on 8.7 miles from the Pusuno-Ahuano bridge to the Ahuano parish, where Balzachicta is located.

"These millions are the reason why some people got so involved in asphalting and stone extraction in the Balzachicta area," says Fiodor Mena. He says that a wall was built to divert the Napo River in the Balzachicta area and that this was confirmed by inspections by the Ministry of the Environment. In addition, this road passes through mining concessions in the Huambuno, Rio Blanco and Ahuano areas. The residents are still wondering who the real beneficiaries are.

In April 2023, the operating permits for the concession were finally approved by the Prefecture of Napo. "We already gave them the permit, they had complied with the paperwork they had to present, and it was a request from some residents, hotel and lodge owners who said they would benefit from the road," says Mena with a disappointed half-smile. Then, with the change of authorities (on April 2, 2023, the Vice Minister of Environment, Jose Antonio Davalos became the head of this department), Mena was removed from his position.

Maria Belen Noroña, professor at Pennsylvania State University and expert on socio-environmental conflicts in extractive activities, warns that in a few years good quality oil will run out in Ecuador and the government will have to look at which strategic sector can be strengthened to meet the budgetary needs. Mining is in the spotlight.

Mishel Baez agrees, believing that illegal mining is "the spearhead" of the government's discourse that the solution would be large-scale mining, with large investment companies, state-of-the-art technology, and excellent public-private relations. This narrative, says Baez, is a strategy to raise an impeccable image of mining megaprojects such as Condor Mirador and Fruta del Norte, which operate in the south of the country.

"What is not taken into account is that, on a large, medium or small scale, mining will always bring conflicts because it is a forced possession of land, water and natural resources. In our studies, we have been able to see that the same problems of the small mining companies are present in the mega-mining companies. There are equally violated rights. Starting with the fact that no company in the country has complied with the mandate of the Environmental Consultation or the Free, Prior and Informed Consent,” concludes Baez.

Not everything is lost

Since 2021, the strength, presence and insistence of social movements and environmental activists have had an impact. Before the pandemic, the expanded coverage of environmental and climate change issues was not as visible as it is today. Forums and summits of indigenous communities defending their territory are becoming more and more common.

Maria Beatriz Eguiguren is the director of the Observatory of Socio-environmental Conflicts of the Technical University of Loja. This academic institution is also part of the National Council of Defenders of Human Rights and Nature. In a face-to-face meeting, the specialist in social sciences shows all the publications that the Observatory has produced in its 15 years, integrated by an interdisciplinary group that includes ecologists, lawyers and activists.

Their research has allowed them to create their own methodology in order to determine and manage socio-environmental conflicts. It is known as the Obsa methodology.

In a second meeting, this time virtual, with Eguiguren and Fiodor Mena, it is clear that the actions that have been developed in Napo, which began with the claims of less than ten dissatisfied people and in two years achieved the signing of an Environmental Control Resolution in the National Assembly, have not occurred by chance, nor by luck, nor by pure passion.

It has occurred gradually. As Eguiguren explained the methodology, the photos, the videos, the meetings with communities and ancestral inhabitants, the night of guayusa and chicha in Tzawata, the tears and anger in Shiguacocha, the anonymous whispers on the phone, the fighting women of communities such as Serena, Yutzupino and Rio Blanco, Balzachicta came to mind. The visible faces like Sandra, Pepe, Andrés and Fiodor. Anti-mining marches, threats, and hope. Everything is part of a new social stage in which mining is uncomfortable and yet is accommodated. But it is no longer received passively by people in the communities. It is confronted, debated, understood. For Maria Belen Noroña, the explanation lies in the fact that, in the absence of government control, activists have emerged from civil society leading regional struggles against mining which are opening spaces beyond political and national boundaries.

*Names have been changed for the security of the sources.