It is two o'clock in the morning.

The night is infinitely black, heavy, bustling.

People start to arrive. The communal house is rectangular, with no walls, with an earthen floor, and tall bamboo columns. Colorful banners hang from the thatch and fiber-cement roof. Two light bulbs illuminate the visitors with a coppery light.

“Alli puncha”

“Alli puncha”

Women with babies on their backs, men with spears and young people with cell phones shake hands and take their seats. Everyone awaits the beginning of the Guaysupina, a ritual that consists of drinking guayusa early in the morning around a bonfire.

The guayusa that will be shared at three o'clock in the morning on Saturday, March 18, 2023, as the official beginning of the founding festivities of the Kichwa Tzawata - Ila - Chucapi community, boils over charcoal in a burnt pot.

They celebrate their existence, although they have been invisible for over 300 years.

Kambak Wayra Alvardo Andi enters the open room. He greets those who are already seated with a slight smile and talks to one of the women who prepare the traditional tea. Then, the leader of the community sits and looks silently over the fire, his feet anchored to the ground, and a little hunched, as if burdened with the fatigue of those who survive a battle.

Kambak goes over the speech he will give in a couple of hours.

Kambak hopes that everything goes well in these two days of celebration.

Kambak imagines what would happen if, in the vulnerability of the party and the merriment, they were forcibly evicted.

Kambak mentally sketches out the response letter to be drafted for the Regional Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR).

Kambak is there but he's not. Just like his ancestral community.

His gaze is lost in the smoke and the coppery light.

The DJ arrives.

Wasteland

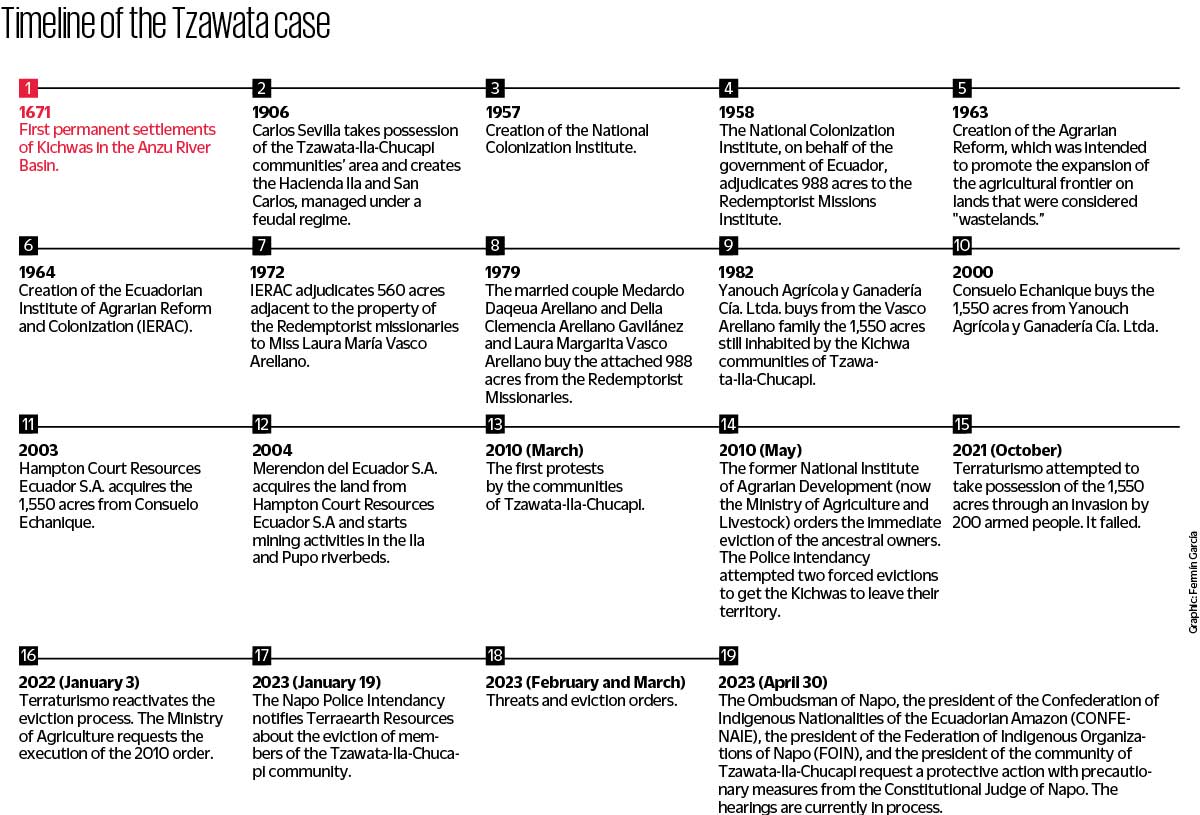

At the end of the 1950s, Ecuador started what became known as the adjudication fair.

In the 1967 Constitution, it was determined that vacant and abandoned lands would be government property that could be transferred to private individuals for the purpose of agriculture, mining and colonization.

On May 22, 1958, the Agrarian Reform and Colonization Institute (IERAC) adjudicated about 488 acres of the former Hacienda Ila to the Redemptorist Missionaries, represented by Reverend Daniel Alarcon Falconí, who on June 7 of the same year received 500 additional acres from the IERAC, according to the Property and Merchandise Register Office of Tena canton, in the Amazonian province of Napo.

Fourteen years later, in 1972, IERAC adjudicated to Miss Laura Margarita Vasco Arellano a property of 560 acres adjacent to the missionaries' land.

In 1979, a married couple, Vasco Arellano, and Laura Margarita Vasco bought the 988 acres from the missionaries and formed a single property of about 1,550 acres on the banks of the Anzu River.

The Kichwa families settled in the same territory in three communities (Tzawata, Ila and Chucapi) and were not aware of these transfers of deeds and signatures. They continued to live in their tall cane houses while working the land for self-consumption and bartering with neighboring communities. They continued to drink and bathe in the river's crystal clear water.

Kichwa teenagers canoe in the Napo River. Photo/Shutterstock

They had no way of knowing about these transactions. The villagers had no roads to communicate with the outside world. Everything was done by inland waterway or by narrow roads that they traveled on foot for hours until they reached Tena, the nearest city. They did not know about laws or allotments. They were isolated, repeating what their grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents did. The community preserved its language (Kichwa), its ancestral customs of hunting, fishing and planting yucca and plantain, and its sacred rituals.

While life continued in the community, the 1,550 acres continued to pass from hand to hand in the offices of the Tena Land Registry.

In 1982, Yanouch Agrícola y Ganadería Cía. Ltda. bought the property from the Vasco Arellano family. No one from the company came to Tzawata to take material possession. In 2000, Consuelo Donoso Echanique bought the hacienda from Yanouch. Three years later, Donoso sold the property to the mining company Hampton CourtResources Ecuador S.A. which, in 2004, transferred the rights to the company Merendon del Ecuador.

And then the conflict began.

Merendon entered the community with the intention of developing tourism projects. When it found out that there was gold in the subsoil, the company switched to the mining industry and started mining activities in the Pupo and Ila rivers.

Gold mining was carried out from 2006 to 2008, until the Mining Mandate approved by the Constituent Assembly forced the suspension of all mining concessions to be renegotiated under the new mining law.

The community says it received minimal compensation and the germ of social division haunted the territory during the time that mining began on the banks of their rivers. Tzawata has always been against Merendon's presence in what the community claims are its ancestral territories. For their part, leaders of Chucapi and Ila even held conversations with Merendon, claiming that they could never win a legal battle.

“The legal battle process is complicated, exhausting,” says Maria Belen Noroña, professor at Pennsylvania State University, political ecologist, and researcher of socio-environmental conflicts in mining and oil issues. "It requires them to constantly attend meetings, to be criminalized by the environmental defenders, which is why many communities give up, give in or negotiate with extractive companies. In addition, in those years, since 2012, there was a rupture of the Confederation of Indigenous Nationalities of Ecuador (CONAIE) with Rafael Correa's government, who at the same time expelled some NGOs, which weakened the processes of social struggle,” she explains.

Noroña has published articles related to mining, the oil sector, and social disputes. In her analysis of collective action in the Amazon, she refers to the Tzawata case. She emphasizes that this community has achieved legitimacy without owning the land. The strategy has been to create and maintain networks with all types of organizations, social groups, farmers, community groups, international volunteers, foreign institutions, and these alliances are flexible according to the circumstances.

The Ila and Chucapi communities, when they did not receive the expected results, when they had witnessed environmental damage, such as the destruction of some of their sacred sites, forests, rivers and ditches, decided not to continue supporting Merendon and joined the Tzawata movement, forming a united front called Tzawata. They also initiated a series of meetings with CONAIE, FOIN (Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Napo) and other social organizations to protest the contamination of their rivers and the social conflict that was beginning to occur.

Then, they claim that harassment against the community began, with prohibitions on the planting of their crops. Tzawata, seeing their carrying capacity affected by these restrictions, decided to get involved in a complex legal labyrinth. It was recognized as an indigenous community with ancestral roots by the Council for the Development of Nationalities and Peoples of Ecuador (CODEMPE) on July 15, 2011.

On September 10, 2010, the now-defunct Diario Hoy interviewed the general manager of Merendon. Catalina Feijoo Marin made it clear that they were the owners of the 1,550 acres in Hacienda Ila, in the Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola canton. Feijoo told the newspaper that the company had no problem with the surrounding communities but that they were facing an invasion of people who were "outsiders with particular interests.”

Merendon initiated administrative proceedings against the Ecuadorian government in order to provoke the evictions of the community. The former Instituto Nacional de Desarrollo, now the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, ordered the immediate eviction of the inhabitants of Tzawata that same year, with Resolution No. 157-2010 dated May 18, 2010.

There were two attempts. In the first, the public forces managed to destroy some crops. In the second, the entire community resisted and preserved the territory. Those who led the way were women and children, whose weapons were urine and chili splashes, as described by Dr. Maria Belen Noroña, in her case study on the Tzawata resistance.

Kambak confirms it and says that indeed, urine was the children's main weapon. And he shows a photo of that moment.

On January 10, 2011, and in December 2012, Tzawata-Ila-Chucapi made two petitions to the Land Under-secretariat of the Ministry of Agriculture regarding the expropriation of the mining company's title. In 2012 Merendon applied for an environmental license from the Ministry of Environment.

Ten years of silence passed, ten years of calm, ten years of peace. Ten years in which Merendon changed its name twice until it became Terraturismo. S.A.

InquireFirst attempted to contact the company, which is not registered with the Superintendence of Companies or the Servicios de Rentas Internas (SRI). There is only an institutional website with a single telephone number that we have called, and we were told that Dr. Aurelio Quito is the consortium of lawyers that advises them. As of press time, we have not been able to contact Dr. Quito.

Fiodor Mena, environmental engineer and former zonal Director of the Ministry of Environment, Water, and Ecological Transition., was present at the hearings for the Tzawata litigation. He confirms that the origin of the company is unclear and that it is often linked to Terraearth Resources, but there is no evidence or basic documents about this company. There is a great sense of mystery surrounding it.

In October 2021, taken by surprise, the inhabitants of Tzawata were attacked by 200 people who arrived with machetes, tents, food, pots, gas tanks, roofs, chainsaws, barbed wire, carbines and even mattresses over their heads.

"Their idea or Terraturismo's was to force us out so they could stay. They said they were coming on behalf of Terraturismo to take over the community. They came with so many things that the police had to confiscate them," recalls Kambak.

Tzawata activated the indigenous guard protocol. People from neighboring communities arrived. An undeclared war broke out and the outsiders were unable to evict the Kichwas from the old Hacienda Ila.

For Noroña, this is Tzawata's main strategy, to activate the network at the exact moment of the eviction attempts. "They know when they are going to be evicted and the night before they mobilize their networks. They have learned to manage the territory through their relationships.”

"Thanks to the machete, a colleague did not die," says Kambak after coming out of his thoughts as he prepares to give the speech to start the festivities, that early morning of March 18, 2023. "My colleagues say that, thank God, our warriors did not die. But I say it was thanks to the machete that was not sharp," he says with a trace of anger.

Since that day, men and women in Tzawata have organized in groups of four to guard the three entrances to the community 24 hours a day. Carrying spears and wearing black T-shirts, they have not stopped guarding for a moment.

Tzawata sleeps with one eye open.

"This is exhausting. It's terrible not to be able to live peacefully," Kambak says, his last words before going on stage.

Leonir Dall'Alba was a Brazilian missionary who arrived in Tzawata in 1987 and made a compilation of interviews with the objective of understanding the origin of this Kichwa community. His book Pioneers, Natives and Settlers: El Dorado in the 20th Century was published in 1992. Among the stories is that of Carlos Sevilla's son, one of the landowners, who said that about 80 native families lived on his land, forming clans with the surnames Alvarado, Grefa, Tapuy, Pauchi, Ila, Dahua, Shiguango.

Luis Alfonso Tapuy is 58 years old and lives in Tzawata. His memories overlap with the music that began to play through the big black speaker brought by the DJ for the community's anniversary party.

“This land is ours.” This is the first thing he says. He remembers the long walks he used to take as a child, together with his mother, to sell the products of his farm in Tena. "We used to walk for hours and get our strength from the chicha that people always put on the road.”

His father died at the age of 90 and Luis Alfonso is proud to say he was able to hear from him the whole history of the town since before the government began to allocate the land. "We are not newcomers, we were born here. That is why we fight. If they take us out, where will our children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren live?

Currently, up to four generations live together. In Tzawata, a community census is conducted every year. As of 2023, there are 393 inhabitants, including children and adults, 20 newborns, and 15 pregnant women.

Alex Grefa, a Kichwa musician with a vast career, arrives at the foundation festivities of the Kichwa community Tzawata -Ila -Chucapi. He is well known in the Amazon. He will sing with his bare chest covered with colorful necklaces. A few minutes before the show, he begins to talk and joins the storytelling to add to the memories of Luis Alfonso Tupay. The artist is not from this community, but the experience, the customs, and the long walks are the same.

"I walk far /to get to my community/ I arrive tired/ I ask the women for chicha/ to calm my hunger.”

That is the chorus of one of his musical compositions. He finds it difficult to translate it into Spanish. Grefa only sings in Kichwa. He talks excitedly about Takitamia, the group he has been part of. He recalls one of his biggest hits, cilularmuku: an ode to cell phone use.

Kambak takes the stage and gives a short and forceful speech. He says they will fight for their land, for their ancestors and for their children. That they will give up their lives if necessary.

"Our lives, because our blood is already in this land," Kambak will say at dawn while the Yachak (wise man of the community) will end the feast with the ritual of the ají (chili pepper).

The locals say that one of the community's rivers is called Pupo because they used to bury the umbilical cords of newborn babies on its banks.

With passion, after the speeches, Alex Grefa sang.

After the Tushuna dance, six women dressed in blue become one in a choreography that represents life in the jungle. The people of Tzawata line up in front of the Yachak who is kneeling and has at his feet, on a colorful blanket, chili, nettle, and tobacco. The nettle is for cleansing the body. The tobacco is placed in the nose to purify the breathing, and the chili is placed in the eyes to fill them with strength.

The yachak (wise man) of the Tzawata community performs a ritual of spiritual cleansing in the early morning, an important part of Tzawata festivities. Photo / Remy Pons.

Men, women, and some children take off their shirts as they advance in line. Onlookers crowd around and film their suffering with their cell phones. The Takitamia band's music plays in the background.

Anthropologist Carlos Duche Hidalgo published a 2010 study on historical evidence that in 1671 the Napu Runas, who were the Kichwa ancestors of the current inhabitants of Tzawata, Ila, and Chucalpi, settled in the Anzu River basin due to the fertile lands and because it was a strategic place for river mobility and commercial exchange. There are also petroglyphs that are evidence of primitive inhabitants. Ancient cemeteries and sacred places where rituals such as guayusa and ayahuasca were performed have also been found.

In 2013, the Ombudsman's Office requested precautionary measures from the Tena Canton Judge in favor of Tzawata due to the conflict with Merendon. In the report, there are photos of damage to sacred sites and deforestation in agricultural areas of the community due to the mining activity that took place between 2006 and 2008. The judge did not grant an injunction.

These political decisions are arbitrary, says Noroña, who recalls that between 2010 and 2019, the Ecuadorian government handed over to 82 communities their Title to Ancestral Lands. Some of them then accepted the presence of mining or oil companies. She mentions the Pañacocha case, in which a mestizo community that lived 40 years in that area was given their title, and today supports and has allowed the passage of machinery to the El Edén oil station of Block 12.

“The issue of ancestry is very subjective, as is the denomination of indigenous people. The Constitution says that only 40 years are needed for a community to be able to claim its ancestry, in the Tzawata case there were already anthropological expert reports. I do not know why they ask for additional ones. These concepts allow the government's interests to interfere. In the Tzawata case, they are requesting ancestry in order to expel mining from their lands,” says Noroña.

On January 30, 2022, the Napo Ombudsman's Office, together with Kambak and Human Rights and Nature organizations, again requested a protective action against the government and in favor of the Tzawata community so that they would not be evicted.

"In the Ila River, we fished, there were ceremonies, bathing, and the mountains were sacred. Our ancestors used to live there and from there they obtained energy from the Pachamama. Next to the Pupo River, there was a culturally important cave that was damaged by mining. When we lost the cave, our culture was affected. It was no longer possible to perform rituals, the Yachak no longer had the same energy, and they have gotten sick," said Andres Alvarado, a resident of Tzawata. His testimony is based on the records of an anthropological expert report carried out by the Judiciary Council in 2021, which was used by the Tzawata community for this new protective action lawsuit against the Ecuadorian government for the eviction attempts.

"The lack of these spaces affects new generations. Since our children have not seen, they no longer believe. We have sat down to drink guayusa and ayahuasca, so we have had visions. Now young people don't do it as much as they used to," Alvarado said in the transcript.

Guaysupina ends and the party begins, amid indignation

It is 6 a.m. on March 18, 2023. After cleaning the sage, the organizers distribute banana leaves on the floor of the community hall. On them, they place bowls of soup, cooked plantain and river fish fillets. People sit down and share the food. The music is replaced by the sound of birds and the Anzu River.

The night's indigenous guard arrives and the new shift departs. Those who stayed put their spears aside and get a plate of food. There was nothing new, no one tried to take their land. One day less. One more day.

While everyone eats in the community hall in Tzawata, José 'Pepe' Moreno, president of the Napo social collectives fighting against mining, sits on the riverbank. He is alone, pensive.

He asserts that the division of the communities, in which each settler has a particular title, makes them more vulnerable. Meanwhile, what is happening in Tzawata is an example of how maintaining communal lands, where everyone decides equally and has equal access to water and land, has allowed them to have the strength to face 12 years of eviction attempts.

This organization has requested from the Ministry of Agriculture the eviction resolutions and its position in this litigation in which it is one of the defendants in the new protective action filed by Tzawata. No response was obtained.

For the first time, through the fog of that March morning in 2023, Pepe can be seen smiling, drawing maps in the sand. He knows the province by heart. As well as all the mining concessions, all the illegal operators, and all the legal companies that do not comply with environmental management plans. He lists the polluted rivers, the dead rivers, the rivers to be defended, the names of all the leaders (those in favor of mining and those against it), of the bureaucrats involved, of the institutions, of corruption, of impunity. Pepe Moreno is of Kichwa origin and traces in the sand the biocides that have been denounced for two years. He knows the numbers of the files, of the complaints, of the reports, of the inspections. Why does he do that? Because he cannot do otherwise, because he cannot believe that the peaceful jungle in which he grew up no longer exists. Because he refuses to believe that the dense green of the jungle can be replaced by rocks, craters, and poisoned water. His colleagues call him, and he leaves the shore shouting a concession number.

Four days later, on March 22, 2023, a video went viral that showed how three men surrounded Pepe and beat him up. They were illegal miners who knew he was joining the military in an operation. They knew it was him even though his face was covered by a ski mask. They shouted at him (while holding him by the hair). "Let us work, shit, we are in debt.”

Pepe will say, through WhatsApp, that he is fine and that this proves that there are people infiltrated in the institutions who, just as they warn that there are social collectives watching and denouncing illegal mining, also inform, hours before, about the operations, allowing the machines to be hidden in the forest.

For Fiodor Mena, president of the Association of Environmental Engineers of Ecuador, the damage caused by legal and illegal mining is unimaginable, but he tries to describe it with the seriousness and rigidity of a scientist. "In Napo, 77,890 acres are concessioned to 180 mining companies. Remember this fact," he says.

Mena insists that mining deforests jungles and agricultural areas and endangers food sovereignty. River pollution affects communities that do not have drinking water. He believes that social conflicts increase with changes in life patterns such as migration and an increase in illegal activities. The "washed" soils, he says, are contaminated, losing their fertility and generating economic losses for the government.

Mena calculates: "Those 77,890 acres concessioned to mining companies represent a cost of environmental restoration and environmental services totaling $2.2 billion in 10 years in Napo alone.”

Now, Mena pulls out another piece of data from the gigantic matrix he is looking at on his screen and says that the mining royalties from the so-called ST CTEA Common Fund for mining extraction generate $27,000 per year in Napo. This means that in 10 years the province would receive $270,000.

“Is it profitable? Is it sustainable?” Mena’s questions are followed by a silence that ends the Zoom session.

It is 9 a.m. on March 18, 2023. Tzawata's children knows nothing of these calculations. But they know a lot about the Amazon. Three girls and four boys walk down to the river. They know the path by heart, stone by stone. They want to show us a rock that serves as a slide. They ask us to follow them. They walk quickly, talking in Kichwa to each other. They arrive at the big rock, they walk to the edge and throw themselves into the whirlpool produced by the current. They all laugh. Then they take the curve that brings them back to the shore. They run back and keep on jumping.

Between the rocks, there is a two-year-old girl. Her older sister dares her, but the little girl ignores her and keeps going down. She knows the exact spot where she must stop and look. Her mother, Samanta Aranda, climbs up with three pieces of clothes she washed in the river. The baby follows her. The other children also leave the river and enter Samanta's house through the branches. The hut stands on bamboo pillars. Downstairs there are hanging clothes, a table, a bicycle, and a staircase leading to the second floor where the bedrooms are.

In front of the house, there is a stone fence with charcoal buried in the ground. Four pillars support a thatched roof. This is the kitchen. On one side there are shelves displaying ceramic pots. Samanta makes them for her personal use, and rents them for USD 5, to her neighbors when they have guests. Samanta is from another province. She came to Tzawata as part of the young people from Pastaza who came to fight against the first evictions in 2010 and that is how she met Carlos Aguinda, who was fighting for his land. Samanta stayed and they already have four children: Juan Carlos, Kely, Froilán, and Yali, a two-year-old baby.

The children's faces are painted red. They played with natural dye and kept running through the forest. They take a cocoa, open it and eat it. There are also uvillas. Further on they go around a huge tree that drops the famous huayruro seeds: they are red with black and there are small and big ones. The girls explain that these seeds are used to make bracelets and necklaces that provide protection from bad energy.

The children disappear.

Back at the community house, the beers and the teams for the men's and women's soccer championship are prepared. A solemn session. Community lunch. Continuation of the championship. Traditional games and the chichazo mix.

Kambak rests for a moment on an old truck. He poses for a photo with two friends. He already has an idea of the response he is going to write to the OHCHR.

On Monday, March 20, the hearing on the Protective Action to be filed by the Tzawata community against the Ecuadorian government for not respecting the laws and international treaties that protect the right of ownership of indigenous communities' lands will begin.

Ancestry is fought in courts

Andres Rojas, Doctor of Law, is young, or, at least, he seems to be. He is always dressed casually and has haughty eyes. He is the Ombudsman of the Napo province. Every conversation with him is a class in environmental legislation.

Regarding the Tzawata case, Rojas recalls that Ecuador signed, in 1997, the International Labour Organization Convention 169, which ensures, from the first article, that the access and use of their ancestral lands by indigenous communities that have lived there since before the current state borders will be respected and preserved. This is supported by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, which reinforces the prohibition of evicting indigenous peoples.

Rojas also cites two rulings of the Constitutional Court of Ecuador and two rulings of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, legal tools with which Kambak is familiar.

The indigenous leader had already sent us the letter from the UNHCHR in which the High Commissioner, Jan Jarab, asks the Ecuadorian government to seriously consider revoking the eviction order, at least while the land ownership issue is being resolved.

This international exhortation was issued after Tzawata experienced new eviction attempts, this time by the Napo Police Superintendent, according to document MDG-GNAP-GSC-2023-0068-OF dated March 1, 2023, to which InquireFirst had access. According to the document, Napo Police Superintendent Manuel Paredes Mero requests technical support from the mayor of Carlos Julio Arosemena Tola (canton where Tzawata is located) to carry out an eviction ordered by the Ministry of Agriculture.

In an interview on March 16, 2023, on Britel, a local digital channel, Paredes denied that there was an eviction order, to which Rojas later replied, in the same media, that the documents are in the public domain and that the order is real.

Three weeks later, the 52-year-old police superintendent was arrested, together with the commissioner of the canton Julio Arosemena Tola and three other officers, for selling liquor and beer in discotheques that was seized in several police operations in the province.

Kambak found out because Paredes was one of the public officials who was to participate in the hearings of the protective action initiated by Tzawata on March 20, and he did so from jail. The former superintendent defended the right of the Terraturismo company to keep the title to the 1,550 acres. Years ago, the now imprisoned man was a lawyer for the Tzawata community.

"This superintendent knew the process because he could not act against his clients in the same case," said Rojas, Napo's ombudsman, who insists that "these things can happen here because people sell themselves to the highest bidder."

Rojas wears a bulletproof vest.

Why does he fight so hard for the rights of nature and indigenous communities? His answer is very similar to that of Pepe Moreno. Rojas for a moment gives up his firm lawyer's voice and changes the tone to a genuine whisper that reveals the child who lived running through the Amazon, bathing in its rivers, who refuses to lose that paradise he keeps in his mind.

"It is from the Presidency of the Republic, at the time, that lands belonging to indigenous peoples to whom the right of historical Ancestral Title was adjudicated, and that is why they can appear today before the Constitutional Justice to claim those rights," said the Ombudsman at the end of the first hearing of the protective action of Tzawata against the Ecuadorian government.

On his left side was Kambak, standing silently. To the right was Sandra Rueda, president of the National Council of Human Rights and Nature Defenders, a civil society that includes activists, communities and academics from all over the country.

Rueda was at the Tzawata celebration, at the hearing of the protective action, and on April 11, 2023, she appeared before the National Assembly to denounce "legal" -- she emphasizes the quotation marks -- and illegal activities in 38 new mining fronts in Napo. She also denounced the natural disasters caused by mining due to the lack of control by the responsible institutions.

The girls of Tzawata explained during the festivities of their village on March 18, 2023 the customs and traditions that make their community life unique -- the uses of various plants, the animals that live in the jungle, their school days and their free afternoons among the trees and the cold water of the Anzu River. They were no more than 10 years old, and they were already bartering the products of their families' farms with each other. They were protecting the leaves of the bushes from the happy outbursts of the little ones.

They will be the next generation to decide what to do with their land. If it is still theirs.